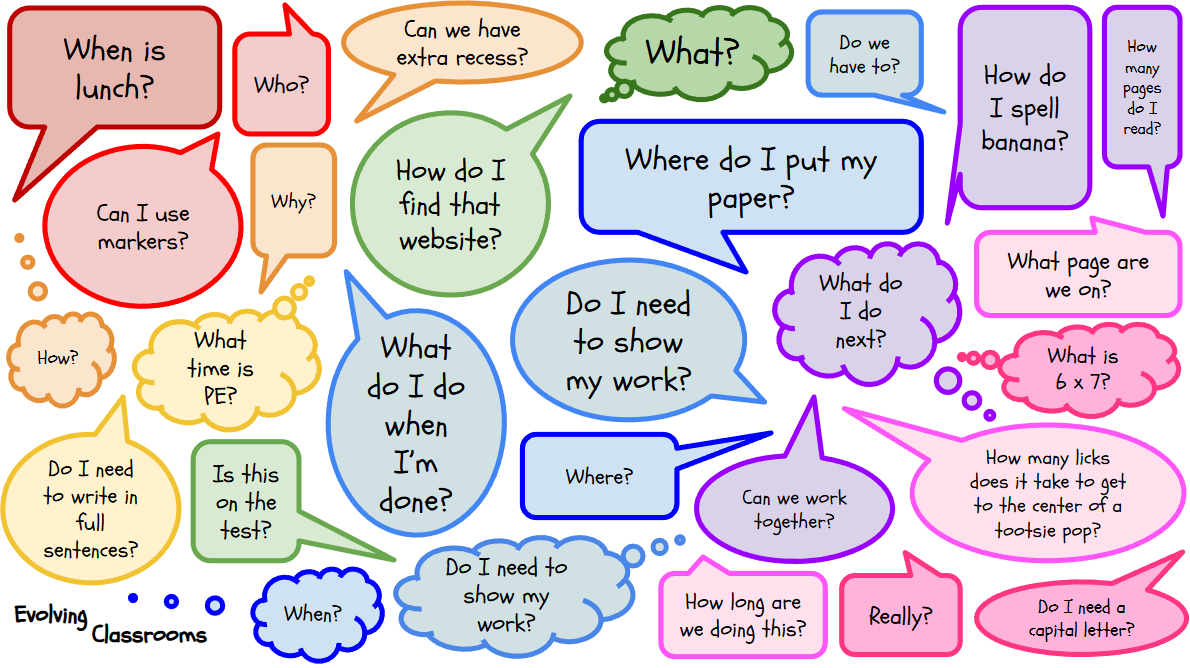

“Ms. Gruskin, how do I do this problem?” “Ms. Gruskin, when is lunch?” “Ms. Gruskin, I can’t find my folder.” “Ms. Gruskin, I don’t know how to do this.” “Ms. Gruskin, where do I put my paper?” “Ms. Gruskin? Ms. Gruskin?? Ms. Gruskin???”

With a morning full of questions like those above, I am sick of hearing my name and am ready to change it by lunch! Sometimes it seems like all I do during the day is answer questions and repeat directions. How many times can I say the same thing?

Not only is this surplus of questions exhausting, but it renders classroom instruction ineffective. I have a relatively small class of just nineteen kids. But when all nineteen need my help at the same time, no one effectively learns anything new. If even half my students have their hands up waiting for my help during classwork, I spend the whole time addressing minor issues rather than monitoring overall progress, checking for understanding, and correcting misconceptions. While I work with one or two students, the others sit there, hands in the air, waiting for me to come over. My students are not actively engaged with the work for large chunks of time. What often makes me so crazy about this, is that they are sitting at tables with their peers! I find I often start to offer help, and a peer who overhears their question will jump in to answer it. Why could they just have asked that classmate in the first place?

Our students are used to seeking adult help. If kids indeed evolved to learn through mixed-age, group interactions, why do students seem to always default to seeking teacher help when they are stuck? How can we change our classrooms so that students value peer-to-peer problem-solving and initiative over the current overreliance on adults.

The Implicit Message of Schooling

Children, under ancestral conditions, did not learn from a single adult teacher. Rather, research shows they likely learned in play-based, mixed-age groups of children (Gray, 2013). Younger children would learn important skills from the older, or more advanced children. The older or more advanced children would solidify skills through teaching and learn about empathy and care-taking (Gray, 2011). Overall, ancestral children learned from others who were naturally working slightly above their level and were able to teach the skill just beyond their ability. Think of this as a natural scaffold in Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978). Under ancestral conditions, adults did not get involved in childhood learning unless specifically requested (Salhil et al., 2019). There were no formal adult teachers.

This self-directed learning is vastly mismatched from our modern school system where adults dictate the day-to-day learning and minute-to-minute activities of children. This control is due to the fact that so many of the skills we need children to master today are more complex than the skills needed by our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Skills such as reading, writing, and mathematics must be taught through some form of direct instruction from an expert (Geary, 1995). As the teacher, I am expected to plan out each minute of the school day and fill it with lessons and activities that will guide my children to mastery of specific grade-level skills and knowledge.

The implicit lessons of this model of schooling are as follows: Teachers are the experts. Students learn from teachers. Students are not teachers. When a student needs help, they should seek that help from teachers, not peers. As a result of this implicit message, kids learn quickly to seek adult help in schools. There is no expectation of a peer being the expert who is able to help. As a result, we see classrooms full of kids who, despite sitting at tables or right next to their peers, all have their hands up waiting on the teacher. Our schooling model reinforces learned helplessness for our students.

Professional Learning Communities (PLCs)

The other concern about this learned helplessness is that it does not help prepare children for their adult lives. When adults need help, they approach a situation very differently. When I have a question about my curriculum, for example, I don’t go to the superintendent or even the principal. I show up in a colleague’s classroom and ask how they teach a certain skill or differentiate a difficult activity. I, along with many others, naturally go to someone who is slightly more experienced than I am. I know that my colleagues, all with different experience, can help with what I am struggling with and probably do it more quickly than someone higher up. I don’t go to the very top unless necessary. If you look around schools, this is the norm. There is not a line of teachers, holding curriculum books, lined up outside the principal’s office waiting for help.

A quote from a recent professional development I attended on Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) stuck out to me. “We should focus on shared teacher efficacy—someone in the room has the answer.” This quote is a great model for teacher collaboration and reflects what often happens in adult workplaces and real-life scenarios. It also mirrors how our hunter-gatherer ancestors learned critical skills. Why then, should we treat our classrooms differently?

Classrooms as PLCs

Part of the challenge of creating classrooms that mirror PLCs has to do with our age-stratified school system. Classrooms are set up with the idea that all children of the same age should be able to learn the same skills at roughly the same pace. In short, schools are like an assembly line. Teachers provide instruction in kindergarten so those children are ready for first grade. First grade teachers build on to that progress so kids are ready for second grade. So on and so forth. All of this work is guided by the state standards and curriculum maps. Children are expected to be uniformly skilled, not experts.

While we cannot rely on any one student to teach their peers complex skills like long division, we really don’t need to. There is a time and a place for learning from experts. Complex secondary skills require some form of explicit, high-quality instruction from an expert (Geary, 1995). I am not advocating for getting rid of teachers.

However, teachers can rely on students to support one another with recall of basic facts, knowledge about procedures, ideas on where to look up information that is unknown, etc. If teachers use peer-to-peer problem solving to tackle these types of basic questions, they would be able to free up time to monitor and support understanding of the more advanced skills that they are currently teaching. Students should not be asked to naturally teach each other all they need to know in school. But, by creating classrooms that mirror the support of a PLC, teachers can rely on children’s evolved educative mechanisms to better the outcomes of their classrooms and make their jobs a little bit easier.

Takeaways

At the end of the day, teachers are resources for our students, but should not be the only resource for students. Each child is different and brings different skills and abilities to our classrooms. Just as our hunter-gatherer ancestors did, modern students benefit from time and space to learn from and support one another. By fostering collaboration and shared problem solving in the classroom, teachers can actually take something off our very full plates.

Teachers cannot expect their eight and nine-year-olds to run a classroom PLC as formally as teachers do. However, there are a few things teachers can do to support age-appropriate peer problem solving:

Model and teach how to seek/provide help. Classrooms function following a teacher’s rules and policies. Without explicit teaching on how to support other learners, children will often just provide the answer for their peers when asked. It is important to model and teach how we want children to use helping skills early on based on what we deem appropriate in our unique classroom environments.

Create a class expectation for asking peers before a teacher. I have seen this done by using saying such as “ask three before me” with the implication being that students must ask three different peers for help before approaching the teacher. Often, this expectation means problems get solved without the teacher ever needing to get involved.

Classify skills that students need during a task as “ask a peer” or “ask a teacher” skills. For example, when teaching a lesson on writing an essay with text evidence to support a claim, a teacher may want to intervene if kids don’t understand how to find appropriate evidence. On the other hand, they may not want to spend their time helping to spell words or reminding students how to use quotation marks correctly—other students can help support these more basic skills.

If we set up expectations in our classrooms where children are expected to rely on one another for support, we can reduce learned helplessness in schools. Doing so creates a learning environment that mimics how our species has evolved to learn and helps prepare students for success in their adult lives. Seeking support from others is a critical skill in the 21st century. I don’t go right to the superintendent with all my questions, children shouldn’t always go right to the teacher.

Just as a teacher Professional Learning Community can thrive with a focus on shared teacher efficacy, a classroom can thrive with a focus on shared student efficacy. Children have evolved mechanisms to learn from peer-to-peer problem-solving. Let’s let them do just that! Maybe by doing so, I won’t feel the need to change my name by lunch!

References

Geary, D. C. (1995). Reflections of evolution and culture in children’s cognition. Implications for mathematical development and instruction. American Psychologist, 50, 24 –37.

Gray, P. (2011). The special value of children’s age-mixed play. American Journal of Play, 3 (4), 500-522.

Gray, P. (2013). Free to learn. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Salali, G.D., Chaudhary, N., Bouer, J. et al. Development of social learning and play in BaYaka hunter-gatherers of Congo. Sci Rep 9, 11080 (2019).

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.