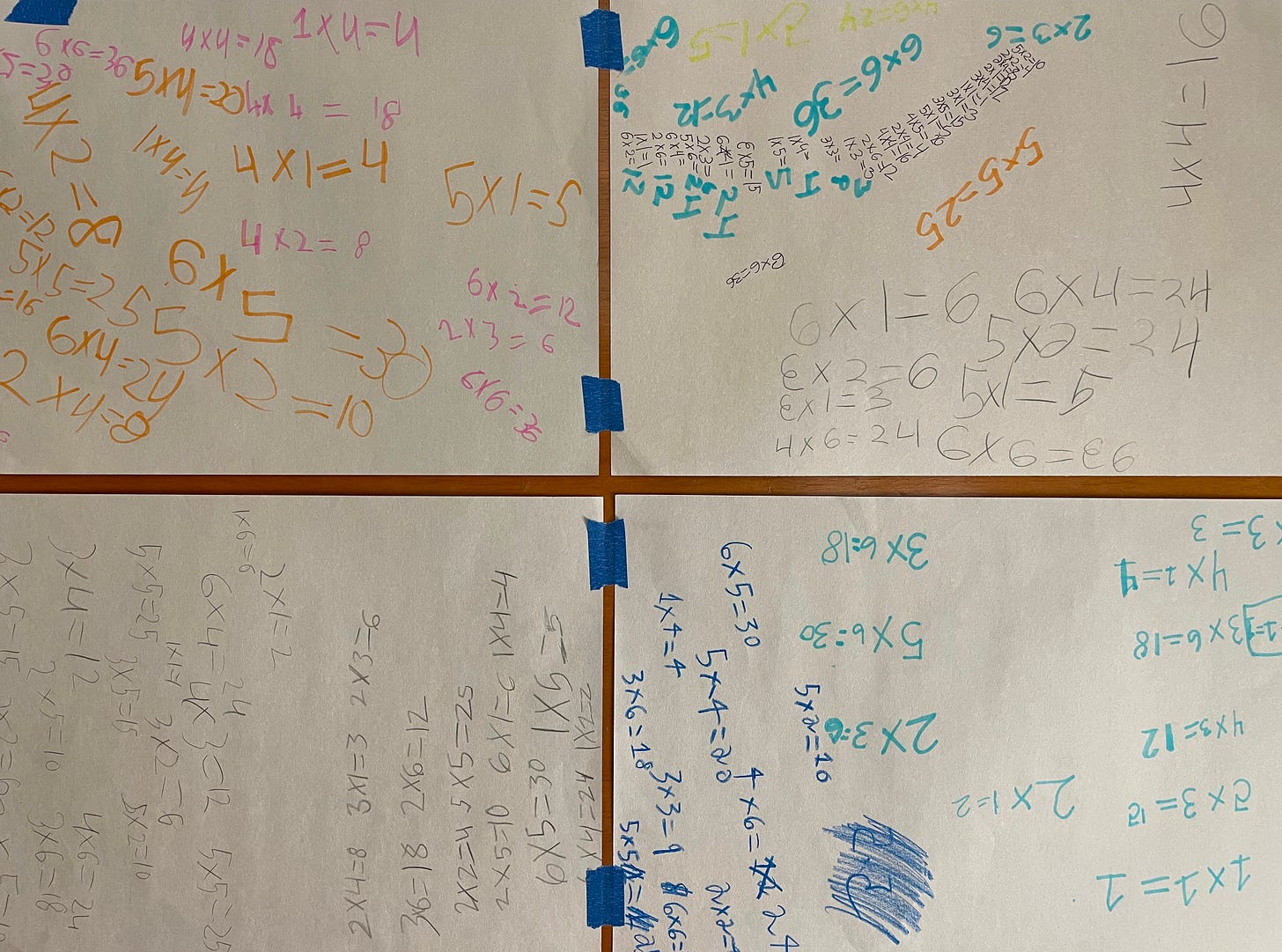

Last week, my third graders were working on the basics of multiplication. Each day we would color in some multiples on a hundred chart, skip count, solve a handful of problems, and do an exit ticket. Rinse and repeat Monday through Thursday. In truth, it was boring! When we attempted a quiz on Thursday, it was apparent that my kids were still struggling to confidently write and solve multiplication equations.

Friday we switched it up. I put out large paper on the tables and gave each child a die. The only direction was to roll twice, multiply, and record their equation. With the simple move away from pencil and workbook to something that more resembled a game, their interest immediately shot up. Instead of struggling through the five questions they had been groaning about doing all week, they happily did dozens of equations in just a few minutes. The room was filled with laughter and conversations about what they were doing and noticing.

My last post spoke about the importance of recess and the crucial social-emotional learning (SEL) skills that kids naturally develop through play. However, SEL skills are not the only skills needed for success in the modern world. Kids must be competent in academic skills such as literacy and mathematics as well. So, what role can play and games serve for acquisition of these skills?

Why Does Play Matter?

Play is how our ancestors evolved to learn primary knowledge skills (Geary, 1995). These would have been skills essential for survival and reproduction in the hunter-gatherer societies that defined most of human evolutionary history. Hunter-gatherer children would watch the adults and mimic what they saw with their peers through play. Importantly in this context, play allowed for a safe environment for children to develop and practice new skills.

As culture advanced rapidly and skills necessary for success became more complex, more explicit instruction did become necessary. However, by creating instruction that is in line with how our species evolved to learn, we are able to take advantage of evolved learning preferences to create better outcomes for modern students (see Gruskin & Geher, 2018). While play on its own is likely not adequate to teach all important modern academic skills (reading, writing, math, etc.), play does have important roles in instruction. When used in conjunction with explicit instruction, play can improve learning outcomes. Importantly, how we couple play with instruction can serve different purposes depending on the desired outcome.

Play After Instruction: Engaged Practice

In the example I gave of the multiplication game, students played after the concept of multiplication was already taught. With the parameters of that specific game, I would not expect students to learn multiplication notation organically without prior instruction. In line with David Geary’s ideas of primary and secondary knowledge, this game only worked since we had already covered that secondary skill with explicit instruction. Kids were now playing the game to practice and further develop their multiplication skills and understandings.

By making the practice into a game, students were much more motivated to engage with the material, they made more connections, and they likely retained more knowledge. Plus, they had fun! In short, using academic practice games after a lesson works because it aligns with how our species evolved to learn. It is collaborative, hands-on, and play based (see Gray, 2013).

Play after instruction has value in the classroom to help with practice and motivation. Teachers can allow time for fluency games like the one described above. We can hang problems around the room for kids to hunt for and solve. We can make use of puzzles with phonics and number skills. There are endless games that exist to reinforce skills in a playful, and thereby evolutionarily relevant, manner.

Play Before Instruction: Building Excitement and Prior Knowledge

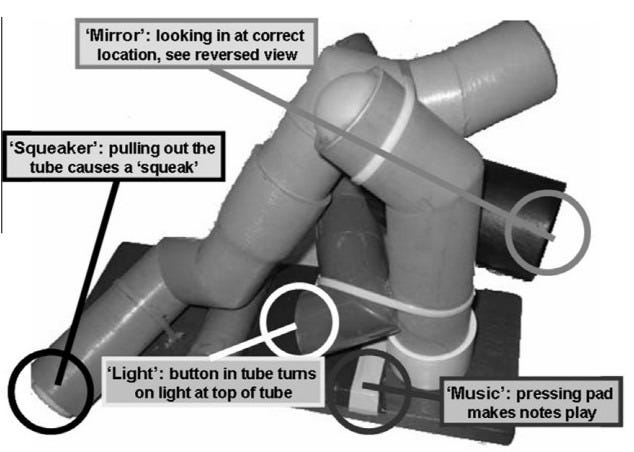

Play can also be used prior to explicit instruction, thereby serving a different purpose. In one of my favorite experimental studies, researchers created a novel toy with hidden functions and introduced it to preschool-aged children in differing conditions.

Some children were explicitly taught about one of the toy’s hidden functions and some children were not. All the children were then left alone to play with the toy. The researchers found that children who were first taught about the toy played with the toy for less time and discovered less of the hidden functions than the children who did not receive any instruction (Bonawitz et. al., 2011).

Think about the implications for classroom learning! Children are intrinsically motivated to learn and explore through play. In doing so, they are able to learn about materials or information provided prior to explicit teaching. Explicit instruction could then be provided after the play experience to ensure all kids learn the academic secondary knowledge skills. This structure is natural and exciting. However, if we skip the play and jump right into lessons and instruction, we may be decreasing students’ motivations to learn and explore independently. If we want to both teach important modern skills and develop lifelong learners, exploratory play may be crucial to those dual outcomes.

Here’s a simple example: when I taught kindergarten I would put out the math manipulatives in the morning for the kids to play with after they unpacked. We had connecting cubes, counting bears, small blocks, geometric shapes, etc. The kids could freely play with these toys that would later be used as math tools. What I found was that when we later brought these tools out for a math lesson, kids were recalling and sharing concepts they had discovered through play. They had organically been counting and comparing stacks of connecting cubes, making patterns with blocks, or building larger shapes and pictures out of the geometric tiles. During play, they discovered and shared these ideas.

When it came time for the explicit instruction, this simple play opportunity had helped level the playing field of background knowledge. Each child, regardless of their prior experiences outside of school, had some connection to the content. This play opportunity also motivated the kids to ask questions about what they previously discovered and created excitement for using these tools for learning. At the end of the day, it was easier to teach the academic skills after the kids had this opportunity for exploratory play. They were ready to learn.

Takeaways

Play on its own is likely not enough to teach kids all they need to know for success in the modern world. Explicit instruction in secondary skills (math, literacy, etc.) is necessary. However, by providing opportunities for play in connection with explicit instruction, teachers are able to make use of children’s evolved motivations to learn through play to practice a skill or develop background knowledge and interest.

To sum it up, here are my suggestions for using play as a teacher:

Allow time for games in the classroom! Kids have evolved to learn through playful, hands-on methods. Even if they are not learning a new skill, they will be more motivated to practice relevant academic skills through play.

Make games collaborative. Kids sharing ideas helps garner excitement and motivation for learning. It also creates more opportunities to practice the social emotional skills that kids naturally learn through play.

Allow for exploratory play before learning. If given the chance to play, kids will likely come to a lesson more prepared and motivated for learning.

I want to stress that nothing said here is revolutionary. The use of play and games in the classroom is by no means new or novel. However, many teachers find it is often difficult to justify time for play in our tighter and tighter packed schedules. Play looks messy and is often loud. When push comes to shove, many teachers may choose to skip a game and go right to the next lesson or subject because they believe the lessons are the priority. But to truly make a lesson meaningful, play and instruction should go hand-in-hand. It is well worth it to spend the time on play and games. Let the kids play!

References

Bonawitz, E., Shafto, P., Gweon, H., Goodman, N.D., Spelke, E., & Schulz, L. (2011). The double-edged sword of pedagogy: Instruction limits spontaneous exploration and discovery. Cognition, 120, 322-330.

Geary, D. C. (1995). Reflections of evolution and culture in children’s cognition. Implications for mathematical development and instruction. American Psychologist, 50, 24 –37.

Gray, P. (2013). Free to learn. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gruskin, K., & Geher, G. (2018). The evolved classroom: Using evolutionary theory to inform elementary pedagogy. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 12, 1-13.